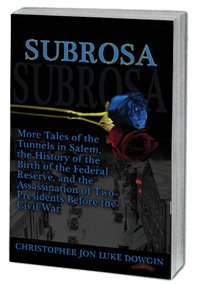

Peanuts, Popcorn, and Presidents

By Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin

Part of the Sinclair Narratives

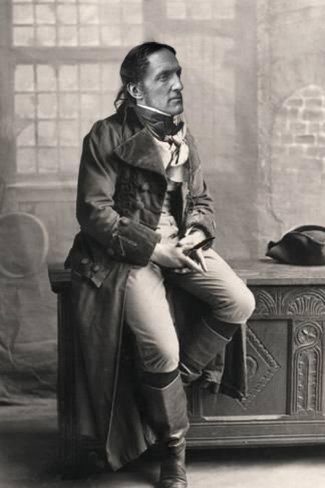

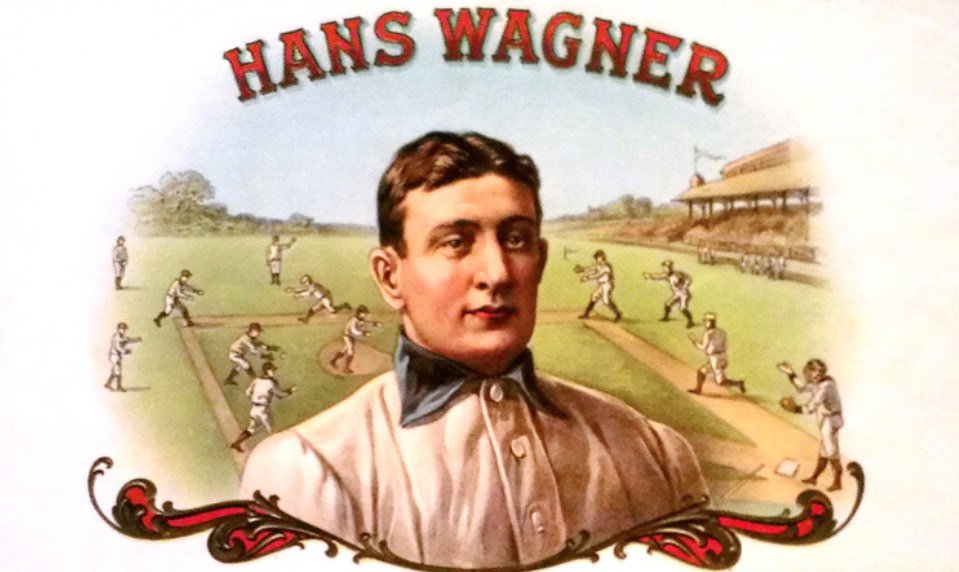

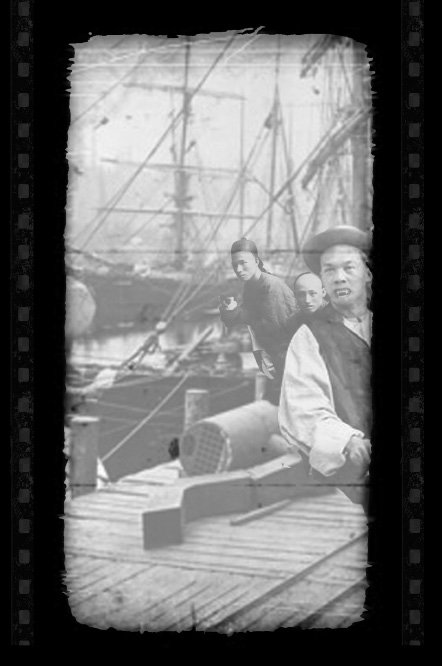

Welcome to another episode in The Sinclair Narratives featuring everyone's favorite immortal, Henry Sinclair, and his third-generation reincarnated Viking crew (sometimes). In this episode, I will tell the story of how three of my closest friends met. It was on the night of the testimonial dinner at Delmonico's for Mr. A.G. Spalding and his party of representatives of American Baseball Players on their arrival to New York City from their tour around the world on April 8th, 1889.

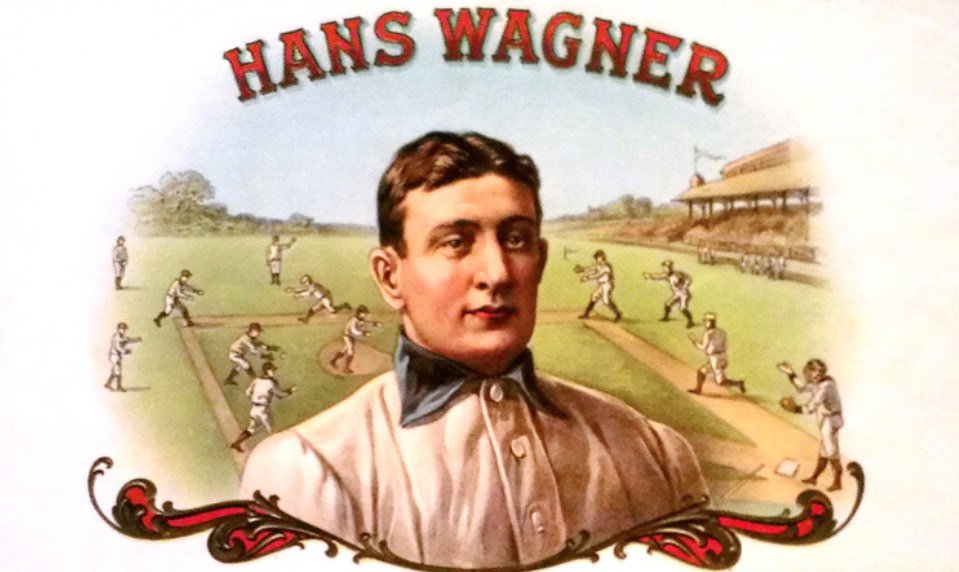

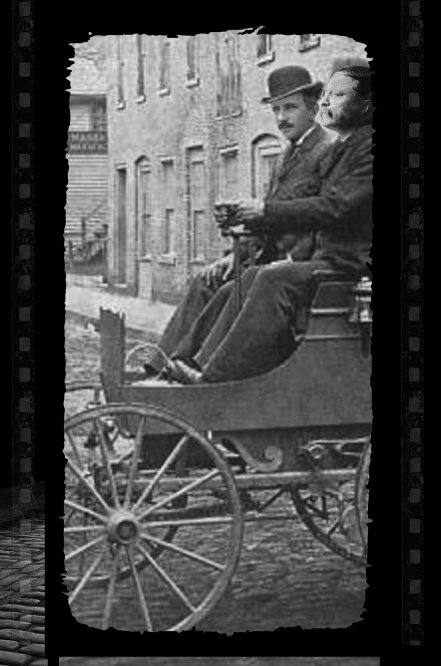

I, Henry Sinclair, had just arrived with my friends Teddy Roosevelt, Bjorn, and Keno Crowninshield the afternoon of the game between the Chicago White Stockings and the All American Team put together by Albert Goodwill Spalding, which went around the world for the last year. Louie drove us down from Salem just in time for the gates to open. Speeding through 4 states at 15mph. Spalding traveled with his two teams spreading baseball and his sporting equipment company from Chicago to Los Angeles and then Hawai'i to Ireland before finishing back in Chicago. Today we had box seats behind home plate at Washington Park. John Montgomery Ward of the All American Team was hitting against Chicago White Stockings' Cap Anson.

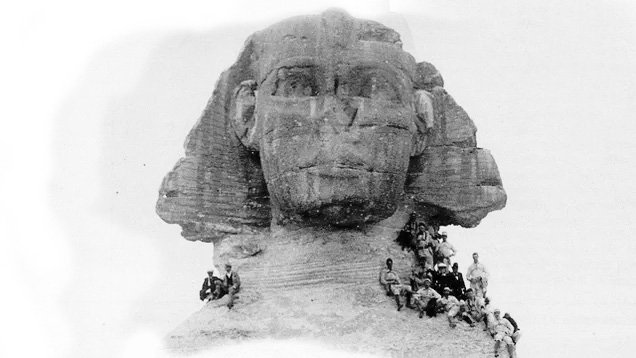

The lines waiting outside of the stadium were huge, for this was the first game in America since they had left Los Angeles for Hawai'i. The world press had followed them and the world was riveted! Many photos had come back of the teams playing in the Coliseum and in front of the Sphinx. They were a home run and they were home again!

Not only were baseball fans in attendance for the game, but our newly elected president. Benjamin Harrison sat in an adjoining box seat with America's favorite author, Mark Twain. Even if the literary critics hated his latest book, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court…

So were all of Manhattan's finest prostitutes to guarantee a home run to anyone willing to pay the cost of the equivalent of three hot dogs and the latest fad, a Coca-Cola. Louie was hoping his hot dog would be relished tonight...

The Chicago team performed poorly. Their catcher arrived well after the game started. Anson was dismayed when Ward kept hitting his players home. Mark Twain in the third inning, poked me in the elbow with his own and said, "Anson is like most politicians, likely to take a bet on any horse in a race, as long as it is not his own. For there is rarely seen a politician, who would place his own money on the people who elected him and paid his salary. Present, presidential, company excluded." The last line he looked at Harrison and smiled, but turned to me with a wink and a laugh. John Healy tossed a no-hitter through six innings for the All American Team while many jokes passed back and forth between the two boxes with me, Keno, and Louie in stitches. Though Teddy never warmed up to him after Mark showed his disdain over our affairs in Samoa at the time. Which TRULY ruffled Teddy's feathers who looked forward to America's impending imperialism. Bjorn was looking at some fellow's girl… By the end of the game, Chicago never pulled ahead and allowed the All-American Team to soundly defeat them.

My friends, won't you join me and Benjamin at Delmonico's tonight?" Twain offered, "The teams are going back to their hotel to put on their sharpest penguin suits and lead a parade to the restaurant within the hour."

"Delmonico's, my cousin is the sous-chef," Louie interjected, "He created all of the dishes, but Ranhofer takes the credit. Like his Baked Alaska—my cousin's Gloucester Cluck Surprise! Lobster Newburgh—Gloucester Lobster!"

"We will be honored," I said as we linked arms and began to strut out of the stadium. Keno followed shaking his head at Louie. Louie punched Bjorn in the arm and he broke his gaze on the girl who was smiling back; her suitor frowned when he had seen her and then glowered at Bjorn. Bjorn just waved over his smile. Teddy was in a huff until Harrison caught his ear about his pursuits in Samoa. Then Teddy seemed to cheer up when he met another capitalist.

There was a bottleneck leaving the stadium. Women were seen running back into the stadium with their husbands and friends chasing after them with concern and sympathy. The rest of the crowd in the back pushed forward into the corridor leading under the bleaches to the exit. We were in the middle of the confusion of the crowd not knowing if they should exit or not. "I fear gentlemen we are like the frog who found the comfort of a hot bath, but too stubborn to lose a good thing before it cooks him. For we are in the stew now."

Teddy ordered us to surround the President as he stopped one of the police he knew from the city. "What the tarnation is going on—get some of your men and protect our President! I fear the anarchists are around."

“No anarchists tonight. It be murder,” said the Irishman.

“Murder, yes. Protect the President before he meets his untimely end, my good man!”

“Not of him, but of her.”

“Who?”

“A drunk who was peeking through a hole behind third base got up off his milk crate and slapped one of the local ‘ladies’ on the shoulder upon commenting on the game. She just fell over. Her coat was closed and she had a catcher’s mitt on. The lad screamed when he saw the blood leaving her mouth. We came upon the scene and found her ovaries inside the mitt—it was the only organs her family will be able to bury with her.”

“Didn’t he notice anything?” Keno asked.

“He said she was there before him, he thought he would be friendly and slap her so she could wake up and go home.”

My heart sank. Louie’s stomach rose to the challenge and lost. Right onto Harrison.

“We tried keeping it a secret, but it must have spread through the pubs back to the park,” explained the emerald officer. “Most of what is preventing the line from moving out is the crowd that heard of the mur-der already.”

“The Leather Apron,” said Louie.

We all just looked at him in confusion.

We sat with Twain and Harrison. Teddy sat as far from Twain as possible. Even though he was upset that the author got to sit next to the President all night with Harrison busting his side open with uproarious laughter. “Bully!” said Teddy as he harrumphed and folded his arms and looked away. Keno just shrugged and was consigned to Teddy’s mood. Bjorn began to mingle with the socialite women...

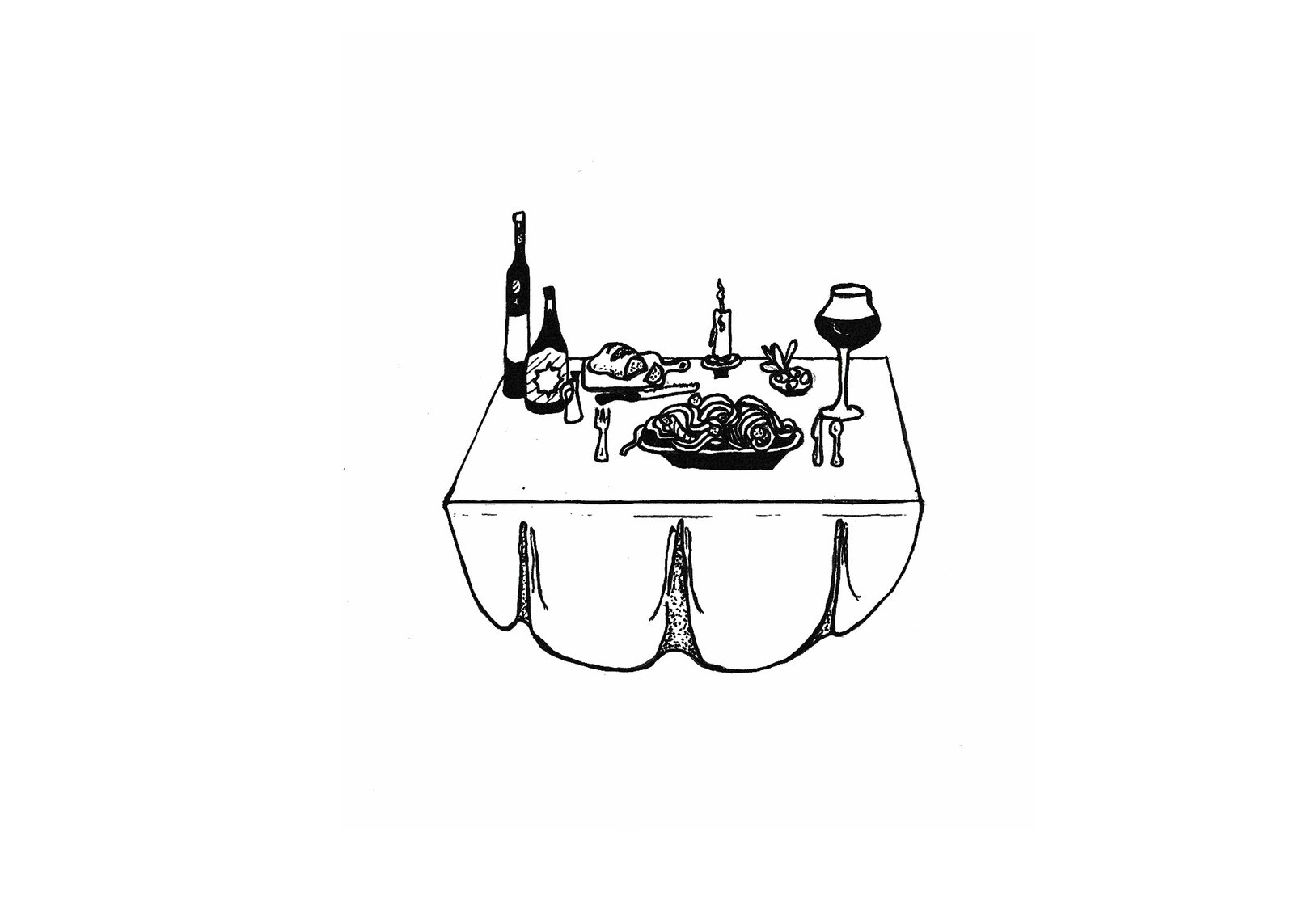

The banquet was held in the anteroom’s second-floor ballroom. An orchestra was in the balcony, playing Yankee Doodle Dandy, decorated with bunting and flags. Photos of the trip were displayed on the walls of the hall—developed on George Eastman’s new Kodak film. Pictures of the team on the Sphinx and in Italy among other places stood out. There were six long tables filled with food and several flower centerpieces. Each table had a three-foot-tall edible statue of several baseball players. Pyramids of sweets! We all received a nine-page souvenir menu. The cost per plate was $10. Each of the 9 innings of courses featured a dish from one of the countries they toured.

Word of the murder hadn’t spread through the hall yet. Many of New York’s finest families were there. Most would never be caught at a baseball game—but dining with the President and Mr. Twain? Even if Twain’s latest book was not doing good…

Dinner ended around 10pm. People began to scurry about as the first speaker began. Chauncey Depew of the New York Central Railroad opened. The Governor and the mayor had sent letters of regret. In attendance were 300 people from Wall Street to the theater district. Many of Chauncey’s Yale and Bonesmen friends were on hand tonight. When he finished the orchestra sparked up again and played Hail to the Chief as Spalding took to the stage. We all had enough by then and began to mingle.

Twain was leading us through New York society, not really stopping to chat with any of them, until he came across this young Croatian. “My good friends, let me introduce you to the greatest mind since da’Vinci,” Twain said as he changed the position of his hand from the man’s right to his shoulder as he stepped to his side and smiled. “Nikola.”

“Charmed,” Nikola said, as he shook my hand.

“I’m quite interested in your work with resonance,” I said.

“You too!” Twain interjected. “It sure did cure my constipation. We need to get more of our politicians to stand on his vibrating machine and they might not all have that sour look of your friend there,” Twain said, as he pointed at Teddy.

“Yes resonance; I got the idea from playing with one of those paddle balls,” Nikola leaned in and said, “They always amazed me. The harder and longer you hit the ball the faster it goes. It’s all in the rhythm.”

“Yes that is what the girls back at Harvard tell me…” commented the young 20-year-old Keno. Not sure if he is still wet behind the ears though; most likely. Bjorn just slapped him on the back, as he shook his head. A fine young woman in black sauntered by and Bjorn was off again.

“Everything has its frequency. Like a hole in a cylinder spinning on a shaft with a fixed jet of air, the faster it spins the louder the alarm. The frequency, you understand? The amount of times an occurrence happens. The frequency,” Nikola explains.

“Yes, me and Tesla frequent the Players Club. In fact, that is where we met. Later we would come here and dine and—that is where I complained about my gosh tooting constipation and he brought me back to his lab and fixed me right up.” Twain paused before he continued looking up from the floor, “ Just shook that shit out of me!”

“You think we can go there now...” Louie asked Nikola.

“Right now I’m working on two coils in which they both have their own capacitor, where the first feeds the second when excited to emit a charge into a gap of air. Once the second coil’s capacitor becomes oversaturated, like a sponge, it will spark into the air. As quickly as the frequency of the second coil empties, the first fills it. Thus you see, electricity flows through the air through great distances.”

I am also working on having a frequency where I aim the current into the magnetic field of the ground, making waves of electricity to circle the globe to feed the first coil without the need for a generator and transformer. I can light bulbs now at a distance. I have the workings to send the voice without telegraph wires and even handwriting, though it’s not stable yet. One day I will be able to shoot beams off the ionosphere. Which will direct my mighty currents to control multiple devices—like one of your yachts young man,” Nikola finished looking at Keno. “I have heard of your yacht races.”

“Yes, young Crowninshield here comes from a long seafaring family—his grand-uncle was once Secretary of the Navy, after his brother turned down the post. A position I hope to serve under one day,” Teddy joined in.

“I heard of your family, yes? Was not one of your kin the man who built, what was it—yes, Cleopatra’s Barge to free Napoleon from St. Helena?” asked Nikola with whimsy. “Some say they transported him not far from here to the Delaware to his brother’s estate.”

“Family tradition says we did,” Keno answers with pride. “We even have his snuff-box and boots that he left behind after leaving ship in a hurry, after an affair ended badly—shipboard romances and all. A relation, Nathaniel West—he was even forced to rescue his other brother Lucien from his clutches...they are a complicated family.”

“Which?” asked Nikola.

“I would dare to say both!” answered Keno.

“I read a plaque about that ship in Hawai’i as I was traveling with the teams,” Twain mused, “Sold to the current king’s grandfather I believe. A ship fit for Emperors and kings.”

“Yes, a sore spot in the family. Many believe we should have kept it.”

“Excuse me, Spalding is giving me that look,” Twain said as he was shaking a few hands in a hurry, “He is rambling, waiting for me to speak next.”

Twain went on about apple pie, baseball, and some light-hearted jabs about his new book. He explained how he came up with the idea for a baseball world tour first. The problem was, that he forgot about it until this moment. He said he had hit a ball in Kansas once, which went through the great plains far out of sight. Then, as he was walking in a straight line in the other direction through the prairie, halfway home, the ball hit him in the face, but he just remembered the occurrence now. He went on, and said the funniest thing about his baseball world tour was that the ball was covered in passport stamps from every country on the same latitude.

Then he went on about a baseball game in his book. It was played by the contemporary kings of King Arthur wearing armor. It drew crowds from all over the world. Even if his book was not gaining any readers from his own home. Now after reading it, I wonder if our new friend Nikola is that Connecticut Yankee who they deemed the Wizard con-fouling Merlin. A loose interpretation of Nikola’s interactions with Edison?

Twain left the stage to much aplomb. He confided to us, later that he had hoped they would not throw any of the food at him from the buffet tables. Louie said he would have enjoyed that if it had been tossed his way.

Then one of the fellow tourists Mark met on the journey in Samoa bumped him, a journalist I think he said.

“Tom. Glad to see you,” Mark said, “How did it go with that Samoan girl—I hope she wasn’t Gaugin aged…”

“I can’t talk now—I’m sorry, I got to run.” With that, he almost bowled Louie over.

Then Twain saw, General Leonard Wood. “Woody, what came over our friend, you know that reporter we found only wearing a hula skirt backwards; well I think it was backwards? Any ideas?”

“Good to see you, Mark,” Wood smiled, “Oh, that hooch the natives made, I was lucky no one caught me. I was told by that girl that I left the hut—with my skirt over my head.”

“Yes, but Tom?”

“Lovely speech. Plain talk from the plains. I’ve got to be going.”

‘Strange,” Mark said with exasperation, “On the island, you could not get him to shut up. All about the Indian Wars and the blankets from that ineffable damned fort in Kansas—Fort Riley from where Custard flew out. You hear Harrison just took Indian Territory away from the Choctaws, Osage, and Cherokee—damndest thing...”

Teddy just shook his head and walked off.

It was during Dewolf Hopper’s oration of Casey at Bat when he finished on the lines ‘but there is no joy in Mudville’ that we heard the screams.

The screams came from the balcony. The orchestra was returning when one of the women noticed a man hanging from the bunting. We made our way forward. There we saw General Wood for a moment before he saw Twain and left in a hurry. Moving up next to Mark was this English gentleman. “God bless his soul,” said the man from Manchester, “I was just talking to him before dinner.”

“I saw him too, but he was in a hurry,” Twain said to his friend, “Did he seem worried when you saw him?”

“No, he was in fine spirits; we began talking about that night with the Native hooch when they found you with the chief’s daughter”

“Enough of that, let me introduce you to my friends,” Twain said, placing his hand on the man’s shoulder, “Teddy, Keno, Louie, and Henry this is Edward Hulton. He is slumming it in exile from his father’s newspaper empire.”

“Edward, Athletic News, glad to meet you!”

“Pleasure, you traveled 360 with Spalding?” I asked.

“Yes from Chicago to Chicago by the end of the week. It looks like I will have another story for my father’s other newsies,” Eddy answered.

“Eddy here is the grandson of the Lord of Manchester, so when I mean slumming it in steerage, I mean slumming it,” Twain continued.

“Not as mighty as one of your knights or kings in your tale Samuel,” Eddy answered modestly with a grin.

“Maybe so—what do you think happened?” I asked.

“When I was spending time with Anson and Ward, he kept following Wood,” Eddy thought.

“Wood joined us at the Presidio, San Francisco wasn’t it. No, after San Francisco he only joined us on the ship to Hawai’i,” Twain interjected.

“Yes, Tom plied him full of bourbon!” Eddy pondered.

“What was he up to? Wood is acting strange tonight, he is spending a lot of time with Chauncey and his young Yale friends. Those fellows who meet in the dark and wear those funny robes…” Keno commented.

“Well, we are at a stand-off against the Germans for Samoa. Harrison during the game was telling me we are about to attack the German fleet at any moment now!” Twain added.

“Bully!” yelled Teddy. Twain just gave him a look and went back to Hulton holding his head.

“Wood probably was here tonight to fill in Harrison on the situation there and Hawai’i,” Twain continued.

“Probably so. We also have a warship in the distance to see which side to come in on in the battle,” Eddy responded without letting on to all he knew.

“Who do you think Tom was working for—Hearst’s muckrakers, Germany, or England?” I asked.

“I wonder if he caught a few ‘foul balls’ in his mouth to keep him quiet,” Louie said as he stuffed his face full of appetizers. “I will start asking my cousin and his staff some questions. Nobody pays attention to the caterers.”

It can’t be, but I saw him skirt the edges of the hall. It could not be! For I killed him with my own sword thirty years ago. Plus, he was too old by his appearance to be reincarnated. How can it be…

It turned out Tom was a fine catcher. They let him down. Hysteria had grasped the hall as someone yelled ‘the girl’ as the room gasped. The chatter became indistinct and agitated like locusts brushing their wings against each other in increasing frequency until they swarmed.

The detail set to protect the event was the first to investigate. The Irishman came in with the Police Commissioner Charles F. McLean. Plus this, Doctor Lazlo. Lazlo examined Tom and found that one of his eyeballs was exchanged for one of the balls believed to be in his mouth. Louie spat out a scallop and winced.

“Any news on the girl’s murder?” Teddy asked of the Emerald Gentleman.

“It seems she was not a prostitute but a German heiress,” the Irish Sargent continued, “Our private is German. He read some letters in her purse going to some man named Tom Delaney.”

Edward just stared at Samuel, “What is the connection?”

“You remember that girl who joined us in Egypt?” Twain asked.

“The one Anson took behind the sphinx trying to solve her riddles?” Eddy asked with raised eyebrows.

“Sarge, did this girl have a brown bob with a heart-shaped scar on her elbow?” asked Twain.

“In fact, she did.”

“It’s her,” Eddy agreed, “She did get into a fight with Wood.”

“In truth, I thought it was about the wood of his bat and if he could score a homer that night…”

“No, it must be about the Samoa Crisis.”

McLean called in an extra detail to protect the President and escorted him back to the Fifth Street Hotel. The baseball players crowded in. Half volunteered to return the President back to his room.

“I know, I’m going to the kitchen now for more of these Greek tarts and info because…” Louie said before we cut him off.

“Nobody notices the caterers,” Teddy, Keno, and I said in unison. Louie just shrugged and left to visit his cousin.

“What is going on in Samoa?” I asked.

“There are spies throughout the Pacific. There is talk about making Hawai’i a state, we would love to evict Germany from Samoa and keep it for ourselves, and there is also talk of taking on Spain for the Philippines. As you know three nations pose their sea cannons at each other, but the battle is really won in the Samoan people’s indifference. Which nation will they stomach? Who will give them less indigestion. After Samoa, we can stage an attack on the Philippines.”

“Bully!” Teddy said as he raised a fist across his chest, “It is about time we had a good war!”

Twain just shook his head once more.

“My father has the Prime Minister’s ear, he is waiting for America to spill its own blood and have England come into the issue looking like the good guy as they manipulate these nations for their own ends,” explains Eddy, “In some circles, they believe we never let America go, we just let you think you won the wars as we took over your banking and thus your politicians.”

“At least now we have an independent treasury. Your hold has weakened on us,” I said.

“The inner circle talks about those we had in Salem and New England who have killed presidents for us.” Eddy continues, “Poison, typhoid has always proven well.”

“Sir, you are talking your way into a bloodied lip,” Teddy stood forward, “I’ll let you know I stood in the ring with Sullivan for 20 rounds when we were younger.”

“Sir, I am not in favor of these Protestants and their politics,” Eddy answered with an open palm on Teddy’s fist. “They have not been nice to us Catholics, though my family has had special dispensation since Henry II to practice our faith.”

“I have dealt with the Junto first hand throughout the years,” I said with my hand on Eddy’s shoulder, “Some I have sent to their makers.”

“So you think Wood is behind this Eddy?” asked Twain.

“Tom did have that fight with him in Melbourne,” Eddy answered.

“What did he find out—that German lady kept close to him, but distanced herself after Cairo,” Twain asked as he tapped his cigar.

“He did head into the Sphinx with a local militia of Bedouins,” Eddy remembered as he scratched his head.

“My family talks about Napoleon and what he had found in Egypt,” chimed in Keno, “Maps and scrolls talking about a Pacific sea passage to South America through Samoa and Hawai’i. Trade of architecture, Cocaine, tobacco, and magic.”

“What magic!” exclaimed Teddy.

“This stuff is truly magic,” Louie said as he walked by chugging some Coca-Cola with his eyes bugging out. Those were the days when Coke was coke.

“Mr. Twain,” I asked as I slid in close, “How well do you know this Edward? Could he be involved in this intrigue for Downing Street? His grandfather, as he says, is royalty. He seems to have kept a close eye on the German, Wood, and Tom.”

“He seems like a good bloke,” Twain said, “Though, for a tipster on the fillies, he seemed more interested in those of us that traveled with the teams than the teams themselves. His father, Edward the Senior, does sway the public’s opinion. Of those on the street and in Parliament through his papers...”

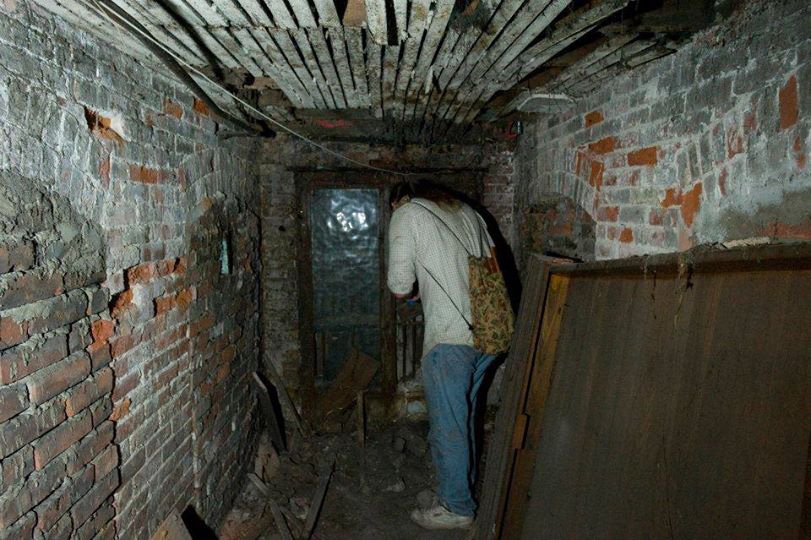

I went to the bar to order a Benedictine and Brandy. The bartender turned his back to grab the bottles from the top shelf and poured me three fingers. As he turned around the bartender transform into Professor Wilmarth and asked, “So any clues?”

“Wood definitely traveled with the teams for some intrigue in Samoa and Hawai’i. Edward has said nothing about what he was up to, as the teams played in London and in his hometown Manchester. He did chum up to Twain. Twain who has our new president’s ear—being an anti-imperialist and all. Wood disappearing into the Sphinx... His argument afterward with the German. Tom shadowing him. Wood a soldier and doctor, he would know how to cleanly sever the organs.”

“Leather Apron,” said the good professor.

“Louie said that,” I asked as I took a sip, “What does that mean?”

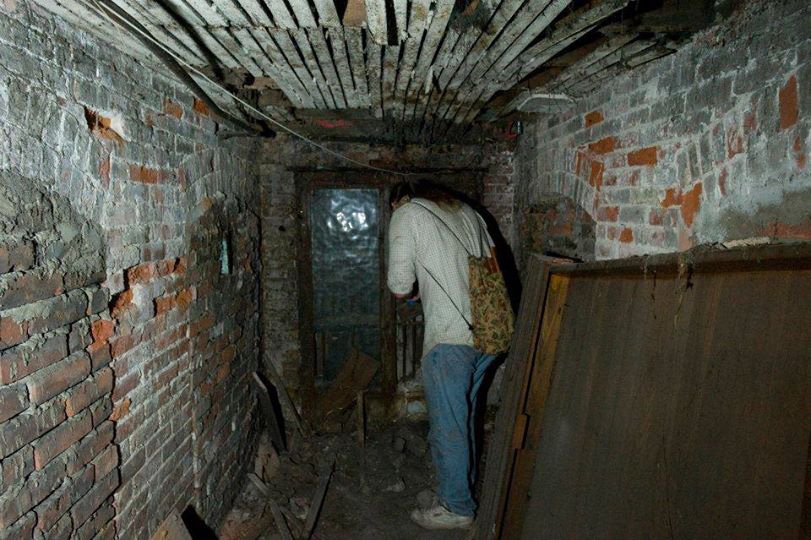

“A year ago in Whitechapel, where George Peabody evicted the wretched to build expensive housing for the poor—yeah, OK. In that neighborhood, five women were murdered with their organs removed. Then it just stopped.”

“You think this person could have come over with the team?”

“You saw that visage from the past?”

“I did see him!”

“Yes, somehow he is alive again.”

“How so?”

“Can’t tell.”

“Why is he here? Is it for the President? I killed him for his complicity in President Taylor’s death.”

“So it would have seemed, though he is here again.”

“He was an agent for the Essex Junto and their overseers in London; could he be working with this Eddy that Twain is friends with?”

“Remember, the royal family is German.”

“What is with this magic that traveled from Egypt to South America?”

“You think the lady was working for the British? Would Wood kill her for her complicity? He would be handy with a scalpel…”

The Professor turned back to the shelves and spun around and the bartender was there again and the Professor was gone. “If you are looking for someone handy with a scalpel I could suggest a few down at the Five Points.”

“Sorry, the drink got the best of me,” I said as I walked away with the snifter.

Over the edge of my glass, I saw him again sneering at me. As I lowered it, he was gone.

When I got back to the bunch, Teddy and Tesla were talking.

“John L. Sullivan, now that is a man’s man,” Teddy was biting at the bit, “Marquess of Queensberry Rules or bare knuckles if it must—I did fight him back in Cambridge, 20 rounds. I did see him again fight at Ong’s Hat in the Pines as I was staying in Philadelphia.”

“I hear a lot about his protege; an Irishman by the name of Weir,” Nikola pondered, “Is he not so from Boston too?”

“Yes, a fine fighter,” Teddy agrees, “For a featherweight—quick though. Also, Kilrain is up next to take on Sullivan. Bare Knuckles! I out rowed him, Kilrain, on the Charles.”

Keno was talking to Twain about the magic items his family had stories about, “Yes, Napoleon’s men found the Rosetta Stone and set out to translate all they were able to during their Egyptian Campaign. There were stories of a man, a relation, from Salem coming back as a Nosferatu after his encounters with Napoleon. Others of my relation sailed the Emperor from St. Helena, after another was left in his coffin, to seek financial aid from his brother Joseph in New Jersey. He wanted the money to search for some mysterious item he read about on the walls of the Sphinx. Napoleon planned to outfit an exposition through the Polynesian Islands to Tenochtitlan. The world thought he was gone—the fool he left in his place kept drinking orgeat syrup while the British were feeding him Cream of Tartar for a stomach issue. The latter prevented his body from expelling the arsenic from the almonds in the syrup. Thus the arsenic forces him to drink more syrup… The ship my family sailed the Emperor on, after my uncle George died and Richard sold it, was purchased by British agents who sailed it to Brazil and then Hawai’i following some scrolls and maps said to be left on board before we could remove them. After failing to find what they were looking for, they sold the ship to the King of Hawai’i. Funny though, the King and his wife sailed to Brazil before sailing to England where they died mysteriously as Cleopatra’s Barge was scuttled. Were they enticed to seek the item?”

It was getting late, Spalding had settled the party down and the last of the speakers were taking the stage. Spalding was not a man to be upstaged by no mere murder. It was a quarter after one when I saw the ghost again. He just sneered over his shoulder before I lost him in the crowd.

I followed him into the hall, when I saw a service door being closed. I entered, and I only saw his face for a mere second before it all went black. The last thing I saw, was his sneer and that confused look as he fought to focus on his objective, me.

I woke up and found myself in motley, padded leather armor on my chest, and a wolf rib bascinet helmet resembling a catcher’s mask. I was behind King Lot. He was playing catcher; King Arthur was at-bat. Pitching was King Mark of Cornwall.

Mark tossed one; Arthur swung and missed. Lot, just turned to me and stared.

“Strike…” I said.

I looked about and saw the field filled with men in armor. All wearing name tags. There was: King Logris, King Marhalt of Ireland, King Pellam, and King of the Lake in the field. Many other Arthurian kings sat in the dugout. A few royal executioners stood around me, sneering. I felt as if I left no joy in Mudville I would lose—my head. I hoped Arthur was a better batter than Casey; removing the proposition from my control.

Mark threw a screwball; Arthur let it go by.

Everyone looked toward me. Executioners gathered to my left and right. Some with the ax. Others with the kind stroke of a sword. Strike I called; a mild melee between executioners on the two sides broke out. Which only settled down on Arthur’s order.

It was then Arthur pointed to center field. He was calling his shot. The opposing kings slowly made their way deep into the outfield.

Slowly.

Mark waited for them. He threw a mighty curveball. Arthur then produced Excalibur and slashed the ball in half. It landed yards in front of the pitcher. Arthur kicked off his greaves and lumbered toward first. King Mark fell over in his armor. King Lot took his time raising up from his crouch. By the time Lot stood up and made it to the ball, he still had to wait for one of the other kings to return from the outfield to be close enough for him to throw it. By then, Arthur slid into first or fell on it out of exhaustion.

It felt like it was 90 degrees. The kings must have been dying in their armor.

Up next was the King of Hibernia. Mark looked toward Arthur; Arthur was starting toward second, but Mark knew he would not make it for a pitch or two. Mark looked back at the plate; the catcher signaled. Mark nodded; he threw a screwaball. Swing and a miss. The executioners leered; I called a strike. The hooded men fought amongst themselves, with me in the middle. Mark threw his second pitch; it looked high to the left. I called a ball. The executioners for both teams settled down. The catcher signaled; Mark tossed on in. The batter hit a foul. Two strikes. Mark sent a screaming fastball; the King of Hibernia swung, missed, and fell over. Strike I called; the executioners swung, I ducked and ran for first.

Arthur didn’t know any better as he continued for second. I passed him after rounding first with the executioners in tow and gaining. As we went past, we left Arthur in a spin. I rounded third and I ducked one of their axes. It was when I was getting ready to run home, I saw one of the executioners had stayed on the plate. He swung; I slid underneath for a home run.

The Kings called a time out and called together a witan. It was unprecedented. Never before had an umpire ran home. Could Arthur’s side count it as a point? If so, was it legal since I ran home before Arthur? Afterward, the executioners took up their place next to their kings and started pushing against each other. I was left to my own accord, for the moment.

Arthur’s squire, who was the bat boy, walked up with a King Louisville Slugger; and beknighted me, Sir Henry. Before I passed out I had seen the squire pull back his hood to reveal two rabbit ears. It was Harvey the Pooka smiling down at me.

Continued on the Last Story...

So Cthulhu is wondering if no one else wants those Rocky Mountain Oysters?

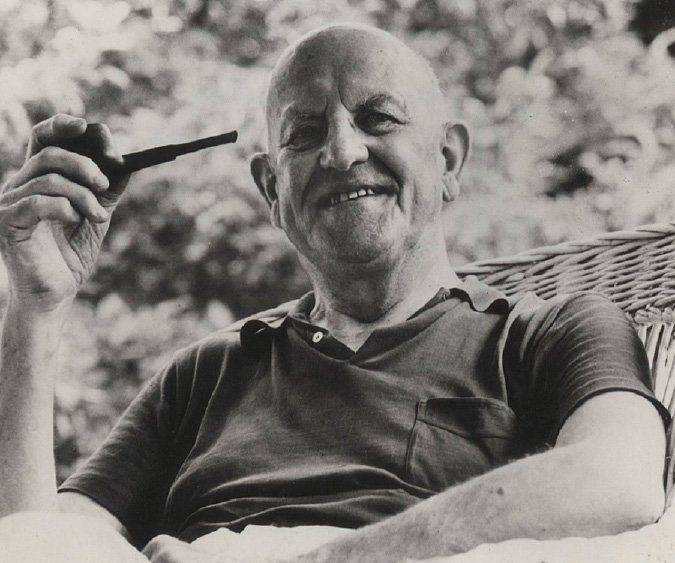

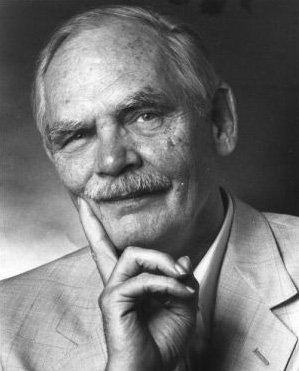

The Celebrated No-Hit Inning

by

Frederik Pohl

This is A TRUE STORY, you have to remember. You have to keep that firmly in mind because, frankly, in some places it may not sound like a true story. Besides, it’s a true story about baseball players, and maybe the only one there is. So you have to treat it with respect.

You know Boley, no doubt. It’s pretty hard not to know Boley, if you know anything at all about the National Game. He’s the one, for instance, who raised such a scream when the sportswriters voted him Rookie of the Year. “I never was a rookie,” he bellowed into three million television screens at the dinner. He’s the one who ripped up his contract when his manager called him, ‘The hittin’est pitcher I ever see’. Boley wouldn’t stand for that. “Four-eighteen against the best pitchers in the league,” he yelled, as the pieces of the contract went out the window. “Fogarty, I am the hittin’est hitter you ever see!”

He’s the one they all said reminded them so much of Dizzy Dean at first. But did Diz win thirty-one games in his first year? Boley did; he’ll tell you so himself. But politely, and without bellowing...

Somebody explained to Boley that even a truly great Hall-of-Fame pitcher really ought to show up for spring training. So, in his second year, he did. But he wasn’t convinced that he needed the training, so he didn’t bother much about appearing on the field.

Manager Fogarty did some extensive swearing about that, but he did all of his swearing to his pitching coaches and not to Mr. Boleslaw. There had been six ripped-up contracts already that year, when Boley’s feelings got hurt about something, and the front office were very insistent that there shouldn’t be any more.

There wasn’t much the poor pitching coaches could do, of course. They tried pleading with Boley. All he did was grin and ruffle their hair and say, “Don’t get all in an uproar.” He could ruffle their hair pretty easily, since he stood six inches taller than the tallest of them.

“Boley,” said Pitching Coach Magill to him desperately, “you are going to get me into trouble with the manager. I need this job. We just had another little boy at our house, and they cost money to feed. Won’t you please do me a favor and come down to the field, just for a little while?”

Boley had a kind of a soft heart. “Why, if that will make so much difference to you. Coach, I’ll do it. But I don’t feel much like pitching. We have got twelve exhibition games lined up with the Orioles on the way north, and if I pitch six of those that ought to be all the warm-up I need.”

“Three innings?” Magill haggled. “You know I wouldn’t ask you if it wasn’t important. The thing is, the owner’s uncle is watching today.”

Boley pursed his lips. He shrugged. “One inning.”

“Bless you, Boley!” cried the coach. “One inning it is!” Andy Andalusia was catching for the regulars when Boley turned up on the field. He turned white as a sheet. “Not the fast ball, Boley! Please, Boley,” he begged. “I only been catching a week and I have not hardened up yet.”

Boleslaw turned the rosin bag around in his hands and looked around the field. There was action going on at all six diamonds, but the spectators, including the owner’s uncle, were watching the regulars.

“I tell you what I’ll do,” said Boley thoughtfully. “Let’s see. For the first man, I pitch only curves. For the second man, the screwball. And for the third man let’s see. Yes. For the third man, I pitch the sinker.”

“Fine!” cried the catcher gratefully, and trotted back to home plate.

“He’s a very spirited player,” the owner’s uncle commented to Manager Fogarty.

“That he is,” said Fogarty, remembering how the pieces of the fifth contract had felt as they hit him on the side of the head.

“He must be a morale problem for you, though. Doesn’t he upset the discipline of the rest of the team?”

Fogarty looked at him, but he only said, “He win thirty-one games for us last year. If he had lost thirty-one he would have upset us a lot more.”

The owner’s uncle nodded, but there was a look in his eye all the same. He watched without saying anything more, while Boley struck out the first man with three sizzling curves, right on schedule, and then turned around and yelled something at the outfield.

“That crazy. By heaven,” shouted the manager, “he’s chasing them back into the dugout. I told that...”

The owner’s uncle clutched at Manager Fogarty as he was getting up to head for the field. “Wait a minute. What’s Boleslaw doing?”

“Don’t you see? He’s chasing the outfield off the field. He wants to face the next two men without any outfield!

That’s Satchell Paige’s old trick, only he never did it except in exhibitions where who cares? But that Boley”

“This is only an exhibition, isn’t it?” remarked the owner’s uncle mildly.

Fogarty looked longingly at the field, looked back at the owner’s uncle, and shrugged.

“All right.”He sat down, remembering that it was the owner’s uncle whose sprawling factories had made the family money that bought the owner his team. “Go ahead!” he bawled at the right fielder, who was hesitating halfway to the dugout.

Boley nodded from the mound. When the outfielders were all out of the way he set himself and went into his windup. Boleslaw’s windup was a beautiful thing to all who chanced to behold it unless they happened to root for another team. The pitch was more beautiful still.

“I got it, I got it!”Andalusia cried from behind the plate, waving the ball in his mitt. He returned it to the pitcher triumphantly, as though he could hardly believe he had caught the Boleslaw screwball after only the first week of spring training.

He caught the second pitch, too. But the third was unpredictably low and outside. Andalusia dived for it in vain.

“Ball one!” cried the umpire. The catcher scrambled up, ready to argue.

“He is right,” Boley called graciously from the mound.

“I am sorry, but my foot slipped. It was a ball.”

“Thank you,” said the umpire. The next screwball was a strike, though, and so were the sinkers to the third man though one of those caught a little piece of the bat and turned into an into-the-dirt foul.

Boley came off the field to a spattering of applause. He stopped under the stands, on the lip of the dugout. “I guess I am a little rusty at that, Fogarty,” he called.

“Don’t let me forget to pitch another inning or two before we play Baltimore next month.”

“I won’t!” snapped Fogarty. He would have said more, but the owner’s uncle was talking.

“I don’t know much about baseball, but that strikes me as an impressive performance. My congratulations.”

“You are right,” Boley admitted. “Excuse me while I shower, and then we can resume this discussion some more. I think you are a better judge of baseball than you say.”

The owner’s uncle chuckled, watching him go into the dugout. “You can laugh,” said Fogarty bitterly. “You don’t have to put up with that for a hundred fifty-four games, and spring training, and the Series.”

“You’re pretty confident about making the Series?” Fogarty said simply, “Last year Boley win thirty-one games.”

The owner’s uncle nodded, and shifted position uncomfortably. He was sitting with one leg stretched over a large black metal suitcase, fastened with a complicated lock. Fogarty asked, “Should I have one of the boys put that in the locker room for you?”

“Certainly not!” said the owner’s uncle. “I want it right here where I can touch it.” He looked around him. “The fact of that matter is,” he went on in a lower tone, “this goes up to Washington with me tomorrow. I can’t discuss what’s in it. But as we’re among friends, I can mention that where it’s going is the Pentagon.”

“Oh,” said Fogarty respectfully. “Something new from the factories.”

“Something very new,” the owner’s uncle agreed, and he winked. “And I’d better get back to the hotel with it But there’s one thing, Mr. Fogarty. I don’t have much time for baseball, but it’s a family affair, after all, and whenever I can help I mean, it just occurs to me that possibly, with the help of what’s in this suitcase. That is, would you like me to see if I could help out?”

“Help out how?” asked Fogarty suspiciously.

“Well I really mustn’t discuss what’s in the suitcase. But would it hurt Boleslaw, for example, to be a little more, well, modest?”

The manager exploded, “No.”

The owner’s uncle nodded. “That’s what I’ve thought. Well, I must go. Will you ask Mr. Boleslaw to give me a ring at the hotel so we can have dinner together, if it’s convenient?”

It was convenient, all right. Boley had always wanted to see how the other half lived; and they had a fine dinner, served right in the suite, with five waiters in attendance and four kinds of wine. Boley kept pushing the little glasses of wine away, but after all the owner’s uncle was the owner’s uncle, and if he thought it was all right.

It must have been pretty strong wine, because Boley began to have trouble following the conversation.

It was all right as long as it stuck to earned-run averages and batting percentages, but then it got hard to follow, like a long, twisting grounder on a dry September field. Boley wasn’t going to admit that, though.

“Sure,” he said, trying to follow; and “You say the fourth dimension?” he said; and, “You mean a time machine, like?” he said; but he was pretty confused.

The owner’s uncle smiled and filled the wine glasses again.

Somehow the black suitcase had been unlocked, in a slow, difficult way. Things made out of crystal and steel were sticking out of it. “Forget about the time machine,” said the owner’s uncle patiently. “It’s a military secret, anyhow. I’ll thank you to forget the very words, because heaven knows what the General would think if he found out. Anyway, forget it. What about you, Boley? Do you still say you can hit any pitcher who ever lived and strike out any batter?”

“Anywhere,” agreed Boley, leaning back in the deep cushions and watching the room go around and around. “Any time. I’ll bat their ears off.”

“Have another glass of wine, Boley,” said the owner’s uncle, and he began to take things out of the black suitcase.

Boley woke up with a pounding in his’ head like Snider, Mays and Mantle hammering Three-Eye League pitching. He moaned and opened one eye.

Somebody blurry was holding a glass out to him. “Hurry up. Drink this.”

Boley shrank back. “I will not. That’s what got me into this trouble in the first place.”

‘Trouble? You’re in no trouble. But the game’s about to start and you’ve got a hangover.”

Ring a fire bell beside a sleeping Damnation; sound the Charge in the ear of a retired cavalry major. Neither will respond more quickly than Boley to the words, “The game’s about to start.”

He managed to drink some of the fizzy stuff in the glass and it was a miracle; like a triple play erasing a ninth-inning threat, the headache was gone. He sat up, and the world did not come to an end. In fact, he felt pretty good.

He was being rushed somewhere by the blurry man. They were going very rapidly, and there were tail, bright buildings outside. They stopped.

“We’re at the studio,” said the man, helping Boley out of a remarkable sort of car.

“The stadium,” Boley corrected automatically. He looked around for the lines at the box office but there didn’t seem to be any.

“The studio. Don’t argue all day, will you?” The man was no longer so blurry. Boley looked at him and blushed. He was only a little man, with a worried look to him, and what he was wearing was a pair of vivid orange Bermuda shorts that showed his knees. He didn’t give Boley much of a chance for talking or thinking. They rushed into a building, all green and white opaque glass, and they were met at a flimsy-looking elevator by another little man. This one’s shorts were aqua, and he had a bright red cummerbund tied around his waist.

“This is him,” said Boley’s escort.

The little man in aqua looked Boley up and down. “He’s a big one. I hope to goodness we got a uniform to fit him for the Series.”

Boley cleared his throat. “Series?”

“And you’re in it!” shrilled the little man in orange. “This way to the dressing room.”

Well, a dressing room was a dressing room, even if this one did have color television screens all around it and machines that went wheepety-boom softly to themselves. Boley began to feel at home.

He blinked when they handed his uniform to him, but he put it on. Back in the Steel & Coal League, he had sometimes worn uniforms that still bore the faded legend 100 lbs. Best Fortified Gro-Chick, and whatever an owner gave you to put on was all right with Boley. Still, he thought to himself, kilts!

It was the first time in Boley’s life that he had ever worn a skirt. But when he was dressed it didn’t look too bad, he thought especially because all the other players (it looked like fifty of them, anyway) were wearing the same thing. There is nothing like seeing the same costume on everybody in view to make it seem reasonable and right. Haven’t the Paris designers been proving that for years?

He saw a familiar figure come into the dressing room, wearing a uniform like his own. “Why, Coach Magill,” said Boley, turning with his hand outstretched. “I did not expect to meet you here.”

The newcomer frowned, until somebody whispered in his ear. “Oh,” he said, “you’re Boleslaw.”

“Naturally I’m Boleslaw, and naturally you’re my pitching coach, Magill, and why do you look at me that way when I’ve seen you every day for three weeks?”

The man shook his head. “You’re thinking of Grand-daddy Jim,” he said, and moved on.

Boley stared after him. Granddaddy Jim? But Coach Magill was no granddaddy, that was for sure. Why, his eldest was no more than six years old. Boley put his hand against the wall to steady himself. It touched something metal and cold. He glanced at it.

It was a bronze plaque, floor to ceiling high, and it was embossed at the top with the words World Series Honor Roll. And it listed every team that had ever won the World Series, from the day Chicago won the first Series of all in 1906 until Boley said something out loud, and quickly looked around to see if anybody had heard him. It wasn’t something he wanted people to hear. But it was the right time for a man to say something like that, because what that crazy lump of bronze said, down toward the bottom, with only empty spaces below, was that the most recent team to win the World Series was the Yokohama Dodgers, and the year they won it in was 1998.

1998?

A time machine, thought Boley wonderingly, I guess what he meant was a machine that traveled in time. Now, if you had been picked up in a time machine that leaped through the years like a jet plane leaps through space you might be quite astonished, perhaps, and for a while you might not be good for much of anything, until things calmed down.

But Boley was born calm. He lived by his arm and his eye, and there was nothing to worry about there. Pay him his Class C league contract bonus, and he turns up in Western Pennsylvania, all ready to set a league record for no-hitters his first year. Call him up from the minors and he bats .418 against the best pitchers in baseball. Set him down in the year 1999 and tell him he’s going to play in the Series, and he hefts the ball once or twice and says, “I better take a couple of warm-up pitches. Is the spitter allowed?”

They led him to the bullpen. And then there was the playing of the National Anthem and the teams took the field. And Boley got the biggest shock so far. “Magill,” he bellowed in a terrible voice, “what is that other pitcher doing out on the mound?”

The manager looked startled. “That’s our starter, Padgett. He always starts with the number-two defensive lineup against right-hand batters when the outfield shift goes.”

“Magill, I am not any relief pitcher. If you pitch Boleslaw, you start with Boleslaw.”

Magill said soothingly, “It’s perfectly all right. There have been some changes, that’s all. You can’t expect the rules to stay the same for forty or fifty years, can you?”

“I am not a relief pitcher. I...”

“Please, please. Won’t you sit down?”

Boley sat down, but he was seething. “We’ll see about that,” he said to the world. “We’ll just see.”

Things had changed, all right. To begin with, the studio really was a studio and not a stadium. And although it was a very large room it was not the equal of Ebbetts Field, much less the Yankee Stadium. There seemed to bean awful lot of bunting, and the ground rules confused Boley very much.

Then the dugout happened to be just under what seemed to be a complicated sort of television booth, and Boley could hear the announcer screaming himself hoarse just overhead. That had a familiar sound, but “And here,” roared the announcer, “comes the all-important nothing-and-one pitch! Fans, what a pitcher’s duel this is! Delasantos is going into his motion! He’s coming down! He’s delivered it! And it’s in there for a count of nothing and two! Fans, what a pitcher that Tiburcio Delasantos is! And here comes the all-important nothing-and-two pitch, and yes, and he struck him out! He struck him out! He struck him out! It’s a no-hitter, fans! In the all-important second inning, it’s a no-hitter for Tiburcio Delasantos!”

Boley swallowed and stared hard at the scoreboard, which seemed to show a score of 14-9, their favor. His teammates were going wild with excitement, and so was the crowd of players, umpires, cameramen and announcers watching the game. He tapped the shoulder of the man next to him.

“Excuse me. What’s the score?”

“Dig that Tiburcio!” cried the man. “What a first-string defensive pitcher against left-handers he is!”

“The score. Could you tell me what it is?”

“Fourteen to nine. Did you see that ?”

Boley begged, “Please, didn’t somebody just say it was a no-hitter?”

“Why, sure.” The man explained, “The inning. It’s a no-hit inning.” And he looked queerly at Boley.

It was all like that, except that some of it was worse. After three innings Boley was staring glassy-eyed into space. He dimly noticed that both teams were trotting off the field and what looked like a whole new corps of players were warming up when Manager Magill stopped in front of him. “You’ll be playing in a minute,” Magill said kindly.

“Isn’t the game over?” Boley gestured toward the field. “Over? Of course not. It’s the third-inning stretch,” Magill told him. “Ten minutes for the lawyers to file their motions and make their appeals. You know.” He laughed condescendingly. “They tried to get an injunction against the bases-loaded pitch out. Imagine!”

“Hah-hah,” Boley echoed. “Mister Magill, can I go home?”

“Nonsense, boy! Didn’t you hear me? You’re on as soon as the lawyers come off the field!”

Well, that began to make sense to Boley and he actually perked up a little. When the minutes had passed and Magill took him by the hand he began to feel almost cheerful again. He picked up the rosin bag and flexed his fingers and said simply, “ Boley’s ready.”

Because nothing confused Boley when he had a ball or a bat in his hand. Set him down any time, anywhere, and he’d hit any pitcher or strike out any batter. He knew exactly what it was going to be like, once he got on the playing field.

Only it wasn’t like that at all.

Boley’s team was at bat, and the first man up got on with a bunt single. Anyway, they said it was a bunt single. To Boley it had seemed as though the enemy pitcher had charged beautifully off the mound, fielded the ball with machine-like precision and flipped it to the first-base player with inches and inches to spare for the out. But the umpires declared interference by a vote of eighteen to seven, the two left-field umpires and the one with the field glasses over the batter’s head abstaining; it seemed that the first baseman had neglected to say “Excuse me” to the runner. Well, the rules were the rules. Boley tightened his grip on his bat and tried to get a lead on the pitcher’s style.

That was hard, because the pitcher was fast. Boley admitted it to himself uneasily; he was very fast. He was a big monster of a player, nearly seven feet tall and with something queer and odd about his eyes; and when he came down with a pitch there was a sort of a hiss and a splat, and the ball was in the catcher’s hands. It might, Boley confessed, be a little hard to hit that particular pitcher, because he hadn’t yet seen the ball in transit. Manager Magill came up behind him in the on-deck spot and fastened something to his collar. “Your intercom,” he explained. “So we can tell you what to do when you’re up.”

“Sure, sure.” Boley was only watching the pitcher. He looked sickly out there; his skin was a grayish sort of color, and those eyes didn’t look right. But there wasn’t anything sickly about the way he delivered the next pitch, a sweeping curve that sizzled in and spun away.

The batter didn’t look so good either same sickly gray skin, same giant frame. But he reached out across the plate and caught that curve and dropped it between third-base and short; and both men were safe.

“You’re on,” said a tinny little voice in Boley’s ear; it was the little intercom, and the manager was talking to him over the radio. Boley walked numbly to the plate. Sixty feet away, the pitcher looked taller than ever. Boley took a deep breath and looked about him. The crowd was roaring ferociously, which was normal enough except there wasn’t any crowd. Counting everybody, players and officials and all, there weren’t more than three or four hundred people in sight in the whole studio. But he could hear the screams and yells of easily fifty or sixty thousand. There was a man, he saw, behind a plate-glass window who was doing things with what might have been records, and the yells of the crowd all seemed to come from loudspeakers under his window. Boley winced and concentrated on the pitcher.

“I will pin his ears back,” he said feebly, more to reassure himself than because he believed it.

The little intercom on his shoulder cried in a tiny voice, “You will not, Boleslaw! Your orders are to take the first pitch!”

“But, listen”

“Take it! You hear me, Boleslaw?”

There was a time when Boley would have swung just—to prove who was boss; but the time was not then. He stood there while the big gray pitcher looked him over with those sparkling eyes. He stood there through the windup. And then the arm came down, and he didn’t stand there. That ball wasn’t invisible, not coming right at him; it looked as big and as fast as the Wabash Cannonball and Boley couldn’t help it, for the first time in his life he jumped a yard away, screeching.

“Hit batter! Hit batter!” cried the intercom. “Take your base, Boleslaw.”

Boley blinked. Six of the umpires were beckoning him on, so the intercom was right. But still and all Boley had his pride. He said to the little button on his collar, “I am sorry, but I wasn’t hit. He missed me a mile, easy. I got scared is all.”

“Take your base, you silly fool!” roared the intercom. “He scared you, didn’t he? That’s just as bad as hitting you, according to the rules. Why, there is no telling what incalculable damage has been done to your nervous system by this fright. So kindly get the bejeepers over to first base, Boleslaw, as provided in the rules of the game!” He got, but he didn’t stay there long, because there was a pinch runner waiting for him. He barely noticed that it was another of the gray-skinned giants before he headed for the locker room and the showers. He didn’t even remember getting out of his uniform; he only remembered that he, Boley, had just been through the worst experience of his life.

He was sitting on a bench, with his head on his hands, when the owner’s uncle came in, looking queerly out of place in his neat pin-striped suit. The owner’s Uncle had to speak to him twice before his eyes focused.

“They didn’t let me pitch,” Boley said wonderingly. “They didn’t, want Boley to pitch.”

The owner’s uncle patted his shoulder. “You were a guest star, Boley. One of the all-time greats of the game. Next game they’re going to have Christy Mathewson. Doesn’t that make you feel proud?”

“They didn’t let me pitch,” said Boley.

The owner’s uncle sat down beside him. “Don’t you see? You’d be out of place in this kind of a game. You got on base for them, didn’t you? I heard the announcer say it myself; he said you filled the bases in the all-important fourth inning. Two hundred million people were watching this game on television! And they saw you get on base!”

“They didn’t let me hit either,” Boley said.

There was a commotion at the door and the team came trotting in screaming victory. “We win it, we win it!” cried Manager Magill. “Eighty-seven to eighty-three! What a squeaker!”

Boley lifted his head to croak, “That’s fine.” But nobody was listening. The manager jumped on a table and yelled, over the noise in the locker room: “Boys, we pulled a close one out, and you know what that means. We’re leading in the Series, eleven games to nine! Now let’s just wrap those other two up, and...”

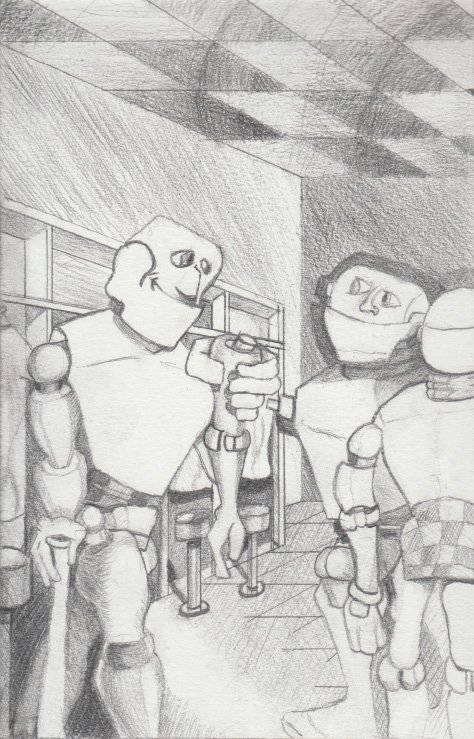

He was interrupted by a bloodcurdling scream from Boley. Boley was standing up, pointing with an expression of horror. The athletes had scattered and the trainers were working them over; only some of the trainers were using pliers and screwdrivers instead of towels and liniment. Next to Boley, the big gray-skinned pinch runner was flat on his back, and the trainer was lifting one leg away from the body

“Murder!” bellowed Boley. “That fellow is murdering that fellow!”

The manager jumped down next to him. “Murder? There isn’t any murder, Boleslaw! What are you talking about?”

Boley pointed mutely. The trainer stood gaping at him, with the leg hanging limp in his grip. It was completely removed from the torso it belonged to, but the torso seemed to be making no objections; the curious eyes were open but no longer sparkling; the gray skin, at closer hand, seemed metallic and cold.

The manager said fretfully, “I swear, Boleslaw, you’re a nuisance. They’re just getting cleaned and oiled, batteries recharged, that sort of thing. So they’ll be in shape tomorrow, you understand.”

“Cleaned,” whispered Boley. “Oiled.” He stared around the room. All of the gray-skinned ones were being somehow disassembled; bits of metal and glass were sticking out of them. “Are you trying to tell me,” he croaked, “that those fellows aren’t fellows?”

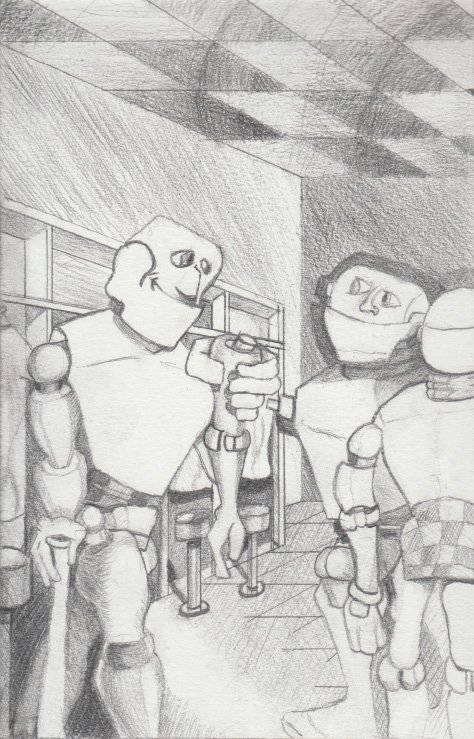

“They’re ballplayers,” said Manager Magill impatiently. “Robots. Haven’t you ever seen a robot before? We’re allowed to field six robots on a nine-man team, it’s perfectly legal. Why, next year I’m hoping the Commissioner to let us play a whole robot team. Then you’ll see some baseball!”

With bulging eyes Boley saw it was true. Except for a handful of flesh-and-blood players like himself the team was made up of man-shaped machines, steel for bones, electricity for blood, steel and plastic and copper cogs for muscle. “Machines,” said Boley, and turned up his eyes.

The owner’s uncle tapped him on the shoulder worriedly. “It’s time to go back,” he said.

So Boley went back.

He didn’t remember much about it, except that the owner’s uncle had made him promise never, never to tell anyone about it, because it was orders from the Defense Department, you never could tell how useful a time machine might be in a war. But he did get back, and he woke up the next morning with all the signs of a hangover and the sheets kicked to shreds around his feet.

He was still bleary when he staggered down to the coffee shop for breakfast. Magill the pitching coach, who had no idea that he was going to be granddaddy to Magill the series-winning manager, came solicitously over to him. “Bad night, Boley? You look like you have had a bad night.”

“Bad?” repeated Boley. “Bad? Magill, you have got no idea. The owner’s uncle said he would show me something that would learn me a little humility and, Magill, he came through. Yes, he did. Why, I saw a big bronze tablet with the names of the Series winners on it, and I saw...” And he closed his mouth right there, because he remembered right there what the owner’s uncle had said about closing his mouth. He shook his head and shuddered. “Bad,” he said, “you bet it was bad.”

Magill coughed. “Gosh, that’s too bad, Boley. I guess I mean, then maybe you wouldn’t feel like pitching another couple of innings well, anyway one inning today, because...”

Boley held up his hand. “Say no more, please. You want me to pitch today, Magill?”

“That’s about the size of it,” the coach confessed.

“I will pitch today,” said Boley. “If that is what you want me to do, I will do it. I am now a reformed character. I will pitch tomorrow, too, if you want me to pitch tomorrow, and any other day you want me to pitch. And if you do not want me to pitch, I will sit on the sidelines. Whatever you want is perfectly all right with me, Magill, because, Magill, hey! Hey, Magill, what are you doing down there on the floor?”

So that is why Boley doesn’t give anybody any trouble anymore, and if you tell him now that he reminds you of Dizzy Dean, why he’ll probably shake your hand and thank you for the compliment even if you’re a sportswriter, even. Oh, there still are a few special little things about him, of course not even counting the things like how many shut-outs he pitched last year (eleven) or how many home runs he hit (fourteen). But everybody finds him easy to get along with. They used to talk about the change that had come over him a lot and wonder what caused it.

Some people said he got religion and others said he had an incurable disease and was trying to do good in his last few weeks on earth; but Boley never said, he only smiled; and the owner’s uncle was too busy in Washington to be with the team much after that. So now they talk about other things when Boley’s name comes up. For instance, there’s his little business about the pitching machine when he shows up for batting practice (which is every morning, these days), he insists on hitting against real live pitchers instead of the machine. It’s even in his contract. And then, every March he bets nickels against anybody around the training camp that’ll bet with him that he can pick that year’s Series winner. He doesn’t bet more than that, because the Commissioner naturally doesn’t like big bets from ballplayers.

But, even for nickels, don’t bet against him, because he isn’t ever going to lose, not before 1999.

First published in Fantastic Universe September 1956

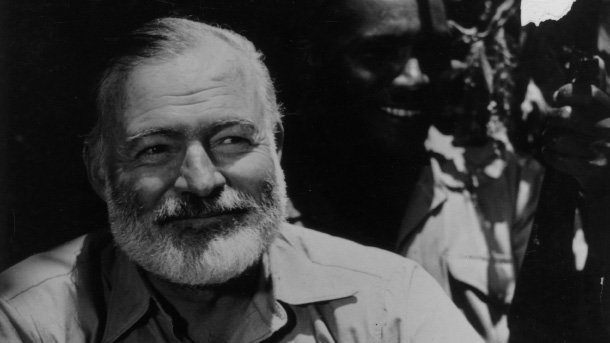

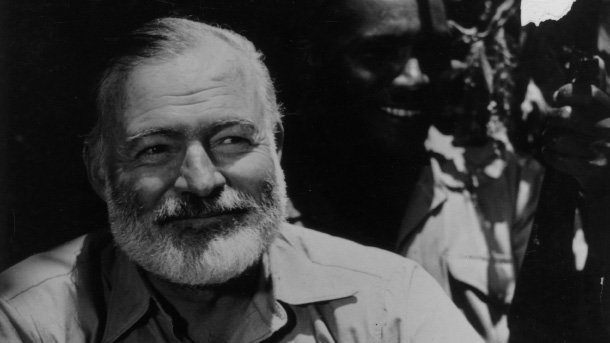

THE END OF SOMETHING

by Ernest Hemingway

In the old days Hortons Bay was a lumbering town. No one who lived in it was out of sound of the big saws in the mill by the lake. Then one year there were no more logs to make lumber. The lumber schooners came into the bay and were loaded with the cut of the mill that stood stacked in the yard. All the piles of lumber were carried away. The big mill building had all its machinery that was removable taken out and hoisted on board one of the schooners by the men who had worked in the mill. The schooner moved out of the bay toward the open lake carrying the two great saws, the traveling carriage that hurled the logs against the revolving, circular saws and all the rollers, wheels, belts and iron piled on a hull-deep load of lumber. Its open hold covered with canvas and lashed tight, the sails of the schooner filled and it moved out into the open lake, carrying with it everything that had made the mill a mill and Hortons Bay, a town.

The one-story bunk houses, the eating-house, the company store, the mill offices, and the big mill itself stood deserted in the acres of sawdust that covered the swampy meadow by the shore of the bay.

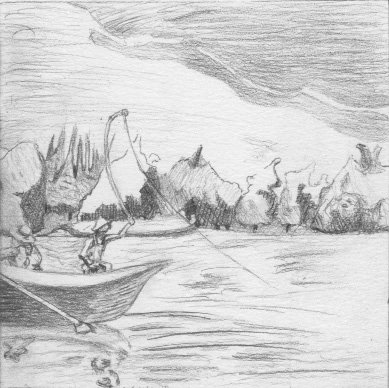

Ten years later there was nothing of the mill left except the broken white limestone of its foundations showing through the swampy second growth as Nick and Marjorie rowed along the shore. They were trolling along the edge of the channel-bank where the bottom dropped off suddenly from sandy shallows to twelve feet of dark water. They were trolling on their way to the point to set night lines for rainbow trout.

“There’s our old ruin, Nick,” Marjorie said.

Nick, rowing, looked at the white stone in the green trees.

“There it is,” he said.

“Can you remember when it was a mill?” Marjorie asked.

“I can just remember,” Nick said.

“It seems more like a castle,” Marjorie said.

Nick said nothing. They rowed on out of sight of the mill, following the shore line. Then Nick cut across the bay.

“They aren’t striking,” he said.

“No,” Marjorie said. She was intent on the rod all the time they trolled, even when she talked. She loved to fish. She loved to fish with Nick.

Close beside the boat a big trout broke the surface of the water. Nick pulled hard on one oar so the boat would turn and the bait spinning far behind would pass where the trout was feeding. As the trout’s back came up out of the water the minnows jumped wildly. They sprinkled the surface like a handful of shot thrown into the water. Another trout broke water, feeding on the other side of the boat.

“They’re feeding,” Marjorie said.

“But they won’t strike,” Nick said.

He rowed the boat around to troll past both the feeding fish, then headed it for the point. Marjorie did not reel in until the boat touched the shore.

They pulled the boat up the beach and Nick lifted out a pail of live perch. The perch swam in the water in the pail. Nick caught three of them with his hands and cut their heads off and skinned them while Marjorie chased with her hands in the bucket, finally caught a perch, cut its head off and skinned it. Nick looked at her fish.

“You don’t want to take the ventral fin out,” he said. “It’ll be all right for bait but it’s better with the ventral fin in.”

He hooked each of the skinned perch through the tail. There were two hooks attached to a leader on each rod. Then Marjorie rowed the boat out over the channel-bank, holding the line in her teeth, and looking toward Nick, who stood on the shore holding the rod and letting the line run out from the reel.

“That’s about right,” he called.

“Should I let it drop?” Marjorie called back, holding the line in her hand.

“Sure. Let it go.” Marjorie dropped the line overboard and watched the baits go down through the water.

She came in with the boat and ran the second line out the same way. Each time Nick set a heavy slab of driftwood across the butt of the rod to hold it solid and propped it up at an angle with a small slab. He reeled in the slack line so the line ran taut out to where the bait rested on the sandy floor of the channel and set the click on the reel. When a trout, feeding on the bottom, took the bait it would run with it, taking line out of the reel in a rush and making the reel sing with the click on.

Marjorie rowed up the point a little way so she would not disturb the line. She pulled hard on the oars and the boat went way up the beach. Little waves came in with it. Marjorie stepped out of the boat and Nick pulled the boat high up the beach.

“What’s the matter, Nick?” Marjorie asked.

“I don’t know,” Nick said, getting wood for a fire.

They made a fire with driftwood. Marjorie went to the boat and brought a blanket. The evening breeze blew the smoke toward the point, so Marjorie spread the blanket out between the fire and the lake.

Marjorie sat on the blanket with her back to the fire and waited for Nick. He came over and sat down beside her on the blanket. In back of them was the close second-growth timber of the point and in front was the bay with the mouth of Hortons Creek. It was not quite dark. The firelight went as far as the water. They could both see the two steel rods at an angle over the dark water. The fire glinted on the reels.

Marjorie unpacked the basket of supper.

“I don’t feel like eating,” said Nick.

“Come on and eat, Nick.”

“All right.”

They ate without talking, and watched the two rods and the fire-light in the water.

“There’s going to be a moon tonight,” said Nick. He looked across the bay to the hills that were beginning to sharpen against the sky. Beyond the hills he knew the moon was coming up.

“I know it,” Marjorie said happily.

“You know everything,” Nick said.

“Oh, Nick, please cut it out! Please, please don’t be that way!”

“I can’t help it,” Nick said. “You do. You know everything. That’s the trouble. You know you do.”

Marjorie did not say anything.

“I’ve taught you everything. You know you do. What don’t you know, anyway?”

“Oh, shut up,” Marjorie said. “There comes the moon.”

They sat on the blanket without touching each other and watched the moon rise.

“You don’t have to talk silly,” Marjorie said; “what’s really the matter?”

“I don’t know.”

“Of course you know.”

“No I don’t.”

“Go on and say it.”

Nick looked on at the moon, coming up over the hills.

“It isn’t fun any more.”

He was afraid to look at Marjorie. He looked at Marjorie. She sat there with her back toward him. He looked at her back. “It isn’t fun any more. Not any of it.”

She didn’t say anything. He went on. “I feel as though everything was gone to hell inside of me. I don’t know, Marge. I don’t know what to say.”

He looked on at her back.

“Isn’t love any fun?” Marjorie said.

“No,” Nick said. Marjorie stood up. Nick sat there, his head in his hands.

“I’m going to take the boat,” Marjorie called to him. “You can walk back around the point.”

“All right,” Nick said. “I’ll push the boat off for you.”

“You don’t need to,” she said. She was afloat in the boat on the water with the moonlight on it. Nick went back and lay down with his face in the blanket by the fire. He could hear Marjorie rowing on the water.

He lay there for a long time. He lay there while he heard Bill come into the clearing, walking around through the woods. He felt Bill coming up to the fire. Bill didn’t touch him, either.

“Did she go all right?” Bill said.

“Oh, yes.” Nick said, lying, his face on the blanket.

“Have a scene?”

“No, there wasn’t any scene.”

“How do you feel?”

“Oh, go away, Bill! Go away for a while.”

Bill selected a sandwich from the lunch basket and walked over to have a look at the rods.

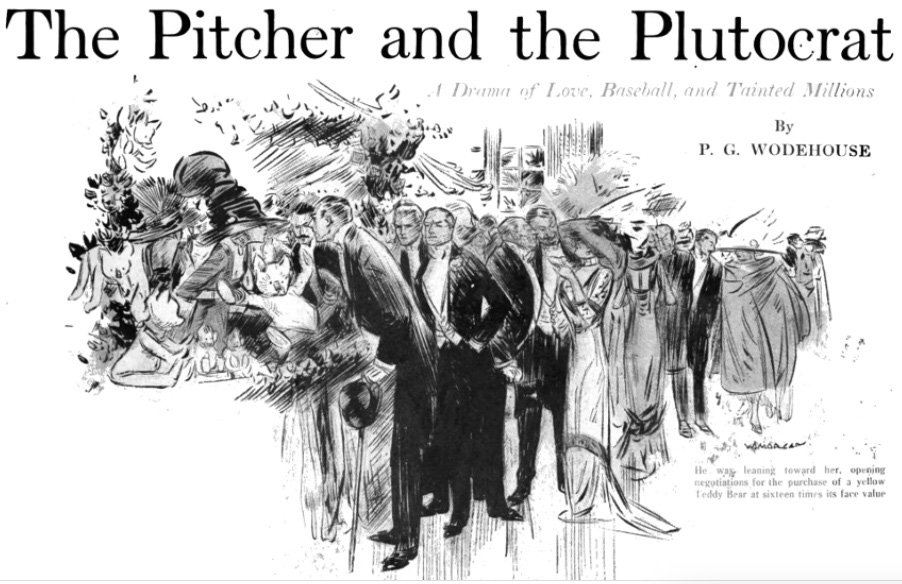

THE main difficulty in writing a story is to convey to the reader clearly yet tersely the natures and dispositions of one’s leading characters. Brevity, brevity—that is the cry. Perhaps, after all, the play-bill style is the best. In this drama of love, baseball, frenzied finance, and tainted millions, then, the principals are as follows, in their order of entry:

Isabel Rackstraw (a peach).

Clarence van Puyster (a Greek god).

Old Man Van Puyster (a proud old aristocrat).

Old Man Rackstraw (a tainted millionaire).

More about Clarence later. For the moment let him go as a Greek god. There were other sides, too, to Old Man Rackstraw’s character; but for the moment let him go as a Tainted Millionaire. Not that it is satisfactory. It is too mild. He was the Tainted Millionaire. The Tainted Millions of other Tainted Millionaires were as attar of roses compared with the Tainted Millions of Tainted Millionaire Rackstraw. He preferred his millions tainted. His attitude toward an untainted million was that of the sportsman toward the sitting bird. These things are purely a matter of taste. Some people like Limburger cheese.

It was at a charity bazaar that Isabel and Clarence first met. Isabel was presiding over the Billiken, Teddy Bear, and Fancy Goods stall. There she stood, that slim, radiant girl, buncoing the Younger Set out of its father’s hard-earned with a smile that alone was nearly worth the money, when she observed, approaching, the handsomest man she had ever seen. It was—this is not one of those mystery stories—it was Clarence van Puyster. Over the heads of the bevy of gilded youths who clustered round the stall their eyes met. A thrill ran through Isabel. She dropped her eyes. The next moment Clarence had bucked center; the Younger Set had shredded away like a mist; and he was leaning toward her, opening negotiations for the purchase of a yellow Teddy Bear at sixteen times its face value.

He returned at intervals during the afternoon. Over the second Teddy Bear they became friendly; over the third, intimate. He proposed as she was wrapping up the fourth Golliwog, and she gave him her heart and the parcel simultaneously. At six o’clock, carrying four Teddy Bears, seven photograph frames, five Golliwogs, and a Billiken, Clarence went home to tell the news to his father.

CLARENCE, when not at college, lived with his only surviving parent in an old red-brick house at the north end of Washington Square. The original Van Puyster had come over in Governor Stuyvesant’s time in one of the then fashionable ninety-four-day boats. Those were the stirring days when they were giving away chunks of Manhattan Island in exchange for trading-stamps; for the bright brain which conceived the idea that the city might possibly at some remote date extend above Liberty Street had not come into existence. The original Van Puyster had acquired a square mile or so in the heart of things for ten dollars cash and a quarter interest in a peddler’s outfit. “The Columbus Echo and Vespucci Intelligencer” gave him a column and a half under the heading: “Reckless Speculator. Prominent Citizen’s Gamble in Land.” On the proceeds of that deal his descendants had led quiet, peaceful lives ever since. If any of them ever did a day’s work, the family records are silent on the point. Blood was their long suit, not Energy. They were plain, homely folk, with a refined distaste for wealth and vulgar hustle. They lived simply, without envy of their richer fellow citizens, on their three hundred thousand dollars a year. They asked no more. It enabled them to entertain on a modest scale; the boys could go to college, the girls buy an occasional new frock. They were satisfied.

HAVING dressed for dinner, Clarence proceeded to the library, where he found his father slowly pacing the room. Silver-haired old Vansuyther van Puyster seemed wrapped in thought. And this was unusual, for he was not given to thinking. To be absolutely frank, the old man had just about enough brain to make a jay-bird fly crooked, and no more.

“Ah, my boy,” he said, looking up as Clarence entered. “Let us go in to dinner. I have been awaiting you for some little time now. I was about to inquire as to your whereabouts. Let us be going.”

Mr. Van Puyster always spoke like that. This was due to Blood.

Until the servants had left them to their coffee and cigarettes, the conversation was desultory and commonplace. But when the door had closed, Mr. Van Puyster leaned forward.

“My boy,” he said quietly, “we are ruined.”

Clarence looked at him inquiringly.

“Ruined much?” he asked.

“Paupers,” said his father. “I doubt if when all is over, I shall have much more than a bare fifty or sixty thousand dollars a year.”

A lesser man would have betrayed agitation, but Clarence was a Van Puyster. He lit a cigarette.

“Ah,” he said calmly. “How’s that?”

Mr. Van Puyster toyed with his coffee-spoon.

“I was induced to speculate—rashly, I fear—on the advice of a man I chanced to meet at a public dinner, in the shares of a certain mine. I did not thoroughly understand the matter, but my acquaintance appeared to be well versed in such operations, so I allowed him to—and, well, in fact, to cut a long story short, I am ruined.”

“Who was the fellow?”

“A man of the name of Rackstraw. Daniel Rackstraw.”

“Daniel Rackstraw!”

Not even Clarence’s training and traditions could prevent a slight start as he heard the name.

“Daniel Rackstraw,” repeated his father. “A man, I fear, not entirely honest. In fact, it seems that he has made a very large fortune by similar transactions. Friends of mine, acquainted with these matters, tell me his behavior toward me amounted practically to theft. However, for myself I care little. We can rough it, we of the old Van Puyster stock. If there is but fifty thousand a year left, well—I must make it serve. It is for your sake that I am troubled, my poor boy. I shall be compelled to stop your allowance. I fear you will be obliged to adopt some profession.” He hesitated for a moment. “In fact, work,” he added.

Clarence drew at his cigarette.

“Work?” he echoed thoughtfully. “Well, of course, mind you, fellows do work. I met a man at the club only yesterday who knew a fellow who had met a man whose cousin worked.”

He reflected for a while.

“I shall pitch,” he said suddenly.

“Pitch, my boy?”

“Sign on as a professional ball player.”

His father’s fine old eyebrows rose a little.

“But, my boy, er— The—ah—family name. Our—shall I say noblesse oblige? Can a Van Puyster pitch and not be defiled?”

“I shall take a new name,” said Clarence. “I will call myself Brown.” He lit another cigarette. “I can get signed on in a minute. McGraw will jump at me.”

This was no idle boast. Clarence had had a good college education, and was now an exceedingly fine pitcher. It was a pleasing sight to see him, poised on one foot in the attitude of a Salome dancer, with one eye on the batter, the other gazing coldly at the man who was trying to steal third, uncurl abruptly like the mainspring of a watch and sneak over a swift one. Under Clarence’s guidance a ball could do practically everything except talk. It could fly like a shot from a gun, hesitate, take the first turning to the left, go up two blocks, take the second to the right, bound in mid-air like a jack-rabbit, and end by dropping as the gentle dew from heaven upon the plate beneath. Briefly, there was class to Clarence. He was the goods.

SCARCELY had he uttered these momentous words when the butler entered with the announcement that he was wanted by a lady at the telephone.

It was Isabel.

Isabel was disturbed.

“Oh, Clarence,” she cried, “my precious angel wonder-child, I don’t know how to begin.”

“Begin just like that,” said Clarence approvingly. “It’s fine. You can’t beat it.”

“Clarence, a terrible thing has happened. I told papa of our engagement, and he wouldn’t hear of it. He was furious. He c-called you a b-b-b—”

“A what?”

“A p-p-p—”

“That’s a new one on me,” said Clarence, wondering.

“A b-beggarly p-pauper. I knew you weren’t well off, but I thought you had two or three millions. I told him so. But he said no, your father had lost all his money.”

“It is too true, dearest,” said Clarence. “I am a pauper. But I’m going to work. Something tells me I shall be rather good at work. I am going to work with all the accumulated energy of generations of ancestors who have never done a hand’s turn. And some day when I—”

“Good-by,” said Isabel hastily, “I hear papa coming.”